Editor’s Note: This article contains graphic images and descriptions.

Christine Pascual’s phone started buzzing while she was at work in a hair salon with messages saying former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte was about to be arrested.

Laxamana, a 17-year-old with dreams of becoming an online gamer, went missing in August 2018 on his way home from a gaming tournament in the northern Philippines.

“His friends who went with him said they were short on money, so they split ways,” his mother recalled. With no word from him in days, she started her own search for her son. “I started looking for him at every computer shop around our area, thinking he was close to home.”

A week later, a letter from the police arrived. It said her son was dead.

She was taken to the morgue and greeted by a sight she had never imagined; her son’s body pierced by six gunshots and covered in bruises.

“When he was young, I’d worried about him being bitten by flies,” she said.

There is another image she will never forget; a photograph the police showed her of Laxamana’s lifeless body on the street where he was gunned down. She remembers his eyes were still wide open.

Pascual said the officers told her he was killed because “he tried to fight back.”

According to a Philippine Inquirer report, Rosales Municipal Police claimed Laxamana was on a motorbike, ignored a police checkpoint, then fired at officers.

“They accused him of horrible, unimaginable things,” said Pascual – who denies her son was a drug dealer and said he didn’t know how to ride a motorbike.

Pascual is determined to seek justice.

With the help of NGOs, she requested a second autopsy and raised money for his funeral. She has also recounted her testimony at senate hearings and public investigations and continues to work with human rights groups to gather evidence for her son.

She even took a case to the Philippines Supreme Court, but it was dismissed.

“We will fight wherever justice takes us…,” she said, “It’s been hard for me to accept my son died without any explanation. He was accused of something and was killed just like that…I hope that can change in this country,” she said.

Pascual is not alone.

A long-awaited arrest

Duterte’s court appearance in the International Criminal Court (ICC) last month is “a sight families of the thousands of victims of the ‘war on drugs’ in the Philippines feared they would never see,” said Amnesty International’s Southeast Asia Researcher Rachel Chhoa-Howard.

“The very institution that former President Duterte mocked will now try him for murder…is a symbolic moment and a day of hope for families of victims and human rights defenders who have for years fought tirelessly for justice despite grave risks to their lives and safety.”

It shows that those accused of committing the worst crimes “may one day face their day in court, regardless of their position,” Chhoa-Howard added.

Duterte ran the Philippines for six turbulent years, during which he oversaw a brutal crackdown on drugs and openly threatened critics with death.

In his inaugural address in 2016, he claimed there were 3.7 million “drug addicts” in the Philippines and said he would “have to slaughter these idiots for destroying my country.”

The figure was more than twice the number of active drug users reported in a 2015 Philippines Dangerous Drug board (DDB) study, which said 1.8 million people – just under 2% of the population – were using drugs.

By 2019, three years into the ‘war of drugs’, the DDB survey estimated 1.6 million people were taking dangerous drugs in the Philippines – an 11% decrease from 2015.

Among many Filipinos, Duterte’s drug war – and his bombastic disregard for the country’s political elites – remained popular for much of his time in office. But the collateral damage caused by so many extrajudicial deaths also mounted.

Many of the victims were young men from impoverished shanty towns, shot by police and rogue gunmen as part of a campaign to target alleged dealers.

According to police data, 6,000 people were killed – but rights groups say the death toll could be as high as 30,000, with innocents and bystanders often caught in the crossfire.

Duterte’s tough approach on drugs prompted strong criticism from opposition lawmakers who launched a probe into the killings. Duterte in turn jailed his fiercest opponent and accused some news media and rights activists as traitors and conspirators.

His blood-soaked presidency ended in 2022 but, three years on, hundreds, if not thousands, of extrajudicial killings have not been accounted for. Victims’ families are often spooked or threatened not to pursue their case in local courts, leaving hundreds in limbo with little to no due process in the Philippines.

To date, only eight policemen had been convicted for five drug war deaths, according to court documents.

The threat of being held to account in the ICC has been hanging over Duterte’s for almost a decade. Prosecutors first said they were watching what was happening in the Philippines in 2016, but it wasn’t until 2021 that a formal investigation was launched.

For years, Duterte – along with his loyal allies and fierce supporters – argued that allegations of wrongdoing should be dealt with by the Philippine justice system, saying the involvement of foreign courts would impede the country’s judicial independence and sovereignty.

As president, he even withdrew the Philippines from the ICC – which took effect in March 2019. That, however, proved to be no protection; the ICC still has jurisdiction for crimes alleged during the years the nation was a member.

Last week, Duterte went from boasting about killing drug dealers to being arrested for crimes against humanity as the ICC finally caught up with him.

In a dramatic arrest, the 80-year-old was outnumbered by local police when he returned to Manila from Hong Kong. After being detained for hours at an airbase, he was put on a plane bound for the Netherlands to face the ICC on charges of crimes against humanity – alleged to have been committed between 2011 and 2019.

On Thursday (March 14), Duterte made his first appearance via video link at The Hague where he appeared tired and slightly uneasy.

His defense lawyer, Salvador Medialdea, called the arrest a “pure and simple kidnapping.”

During the hearing, Presiding Judge Iulia Motoc read Duterte his rights and set September 23 as the date for a hearing to determine whether the evidence presented by the prosecution would be sufficient to take the case to trial.

Left without closure

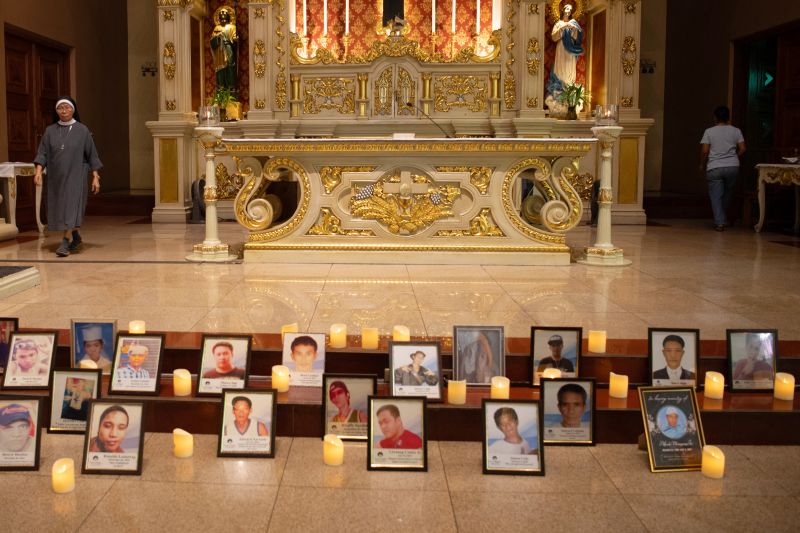

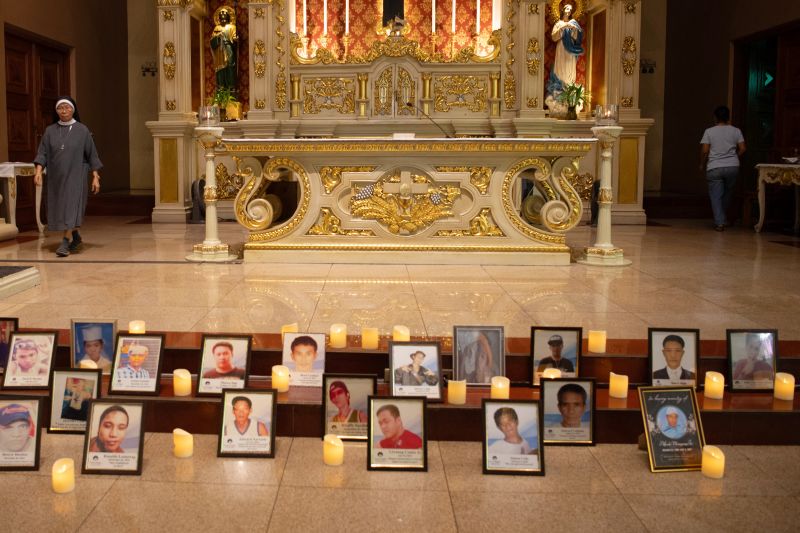

Thousands of lives have been upended by the drug war killings. They not only left devastated parents to bury their children but also left dozens of children as orphans.

Eya was just 9-years-old when both her parents were shot by hooded, uniformed policemen at around three in the morning in August 2016.

Now 18, she and her sister work at a coffee shop in Manila run by families of victims.

”I hope justice will be given to us. And others responsible for the thousands of those who died will also get arrested.”

Cresalie Agosto was at work when her 16-year-old daughter called her in on December 1, 2016 with shocking news.

”Ma, dad has been shot. Please come back,” she heard her daughter say.

Agosto rushed home. Nearby, police had cordoned off an area surrounding her husband’s body.

Witnesses told her they saw two motorbikes each carrying two masked men carrying big, long guns, looking for a man named “Roy”. They asked her husband, Richie Reyes, if he was “Roy”.

She was told that he said he was not the man they were looking for, but they shot him anyway.

“There’s nothing more that we want other than justice and accountability,” Agosto said. “When Duterte was arrested upon arrival his rights were still read aloud to him. For us, our loved ones were greeted with bullets with no explanation.”

Luzviminda Siapo was away from home as migrant worker in Kuwait when tragic news that her 19-year-old son, Raymart, was killed by police in 2017.

Her son was born with clubfoot deformities – a condition which can affect mobility.

A witness who was sleeping in a parked jeepney in an alley told Siapo they heard police yell at Raymart to run away.

“No, I cannot run. I don’t want to run,” Raymart cried out, according to the witness. A gunshot was then heard.

Luzviminda said she wants to see Duterte “rot in jail” for her son’s death.

“He may be in jail, but he is alive unlike my son who died and is no longer with us. I cannot hug him anymore nor talk to him.”